the myth of division between science and art

where science and art meet, understanding deepens

As we grow up, we often hear labels attached to us: “You’re so intuitive and emotional, you belong in the arts,” or “You’re analytical and good with numbers, you should study math or physics.” Even after high school, we’re encouraged to commit to a single career path, usually framed as a choice between two opposing worlds. Most of the time, these paths are treated as mutually exclusive

This dichotomy between “artistic” and “scientific” minds is not supported by research in creativity or cognition. Studies show that the cognitive processes used in artistic creation, such as analogy, visualization, intuition, pattern recognition and conceptual modeling, are the same processes that are needed for scientific innovation (Root-Bernstein 1989). The division we are taught to see in our formative years, is therefore cultural rather than psychological. It reflects educational structures rather than the actual workings of the human brain (Sardar 2000; Root-Bernstein and Root-Bernstein 2004).

Science provides an understanding of universal experience, and art provides a universal understanding of personal experience- both are attempts to make sense of the same world from different angles.

The myth of a divide between science and art

To give concrete examples, influential figures who defined entire fields worked across disciplines without hesitation. (more about embracing our multidimensionality in my first post on substack)

Leonardo da Vinci never stood at a crossroads trying to decide whether he was an artist or a scientist. He simply was both. His paintings grew out of his close study of anatomy, and his anatomical drawings carried the same sensitivity and precision he brought to his art. Even his engineering sketches feel alive, as if the ideas were unfolding on the page. Many artists approached their work with the rigor of scientists.

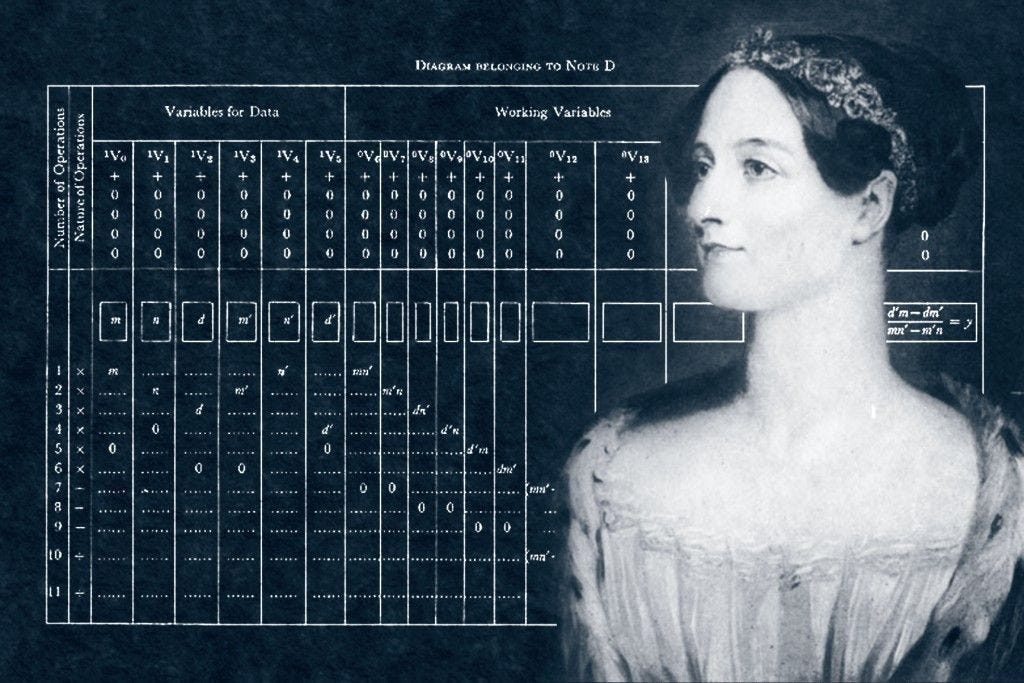

Let’s not forget about Ada Lovelace. She wrote a method for calculating Bernoulli numbers, essentially creating the first computer algorithm. Moreover, she was an incredible writer. She explored the philosophy of machines, the role of imagination in science, and a future where computation could shape music, language, and symbolic expression.

These figures don’t prove that everyone must be both an artist and a scientist. They simply show that the mind is capable of moving fluidly between ways of knowing, and that some of our most remarkable contributions emerged from that fluidity.

The more we look at the figures who genuinely shaped human knowledge, the more this division begins to feel limited. Which points to a deeper truth: the boundary between the two was constructed.

How culture (not the mind) created two separate worlds

The more rigid the systems became, the more these categories defined us. Schools labeled some students as analytical and others as creative. Career paths were presented as mutually exclusive, even though history shows the opposite. Over time, these divisions moved from the structure of institutions into the structure of our identities. We internalized the idea that choosing one meant relinquishing the other.

I want to be clear, I’m not assigning blame here. I’m only trying to rationalize how and where this division might have emerged.

A single strength was allowed to eclipse the rest of a person’s abilities, as if having a talent in one domain automatically disqualified you from another. As if creativity and logic couldn’t coexist. I was always labeled “the creative one,” yet I ended up in scientific research. Proof enough that these labels don’t mean anything.

This is not how the mind operates. We make connections across disciplines without even noticing, taking inspiration from art to understand science and from science to deepen art. Thinking moves fluidly, drawing on whatever helps it make sense of the world. Knowledge itself is shaped by influences from both art and science. Of course, there have been eras when scientific progress accelerated more rapidly, and others when artistic movements dominated but, these shifts reflect history, not hard boundaries about ourselves.

Shared mental qualities of science and art

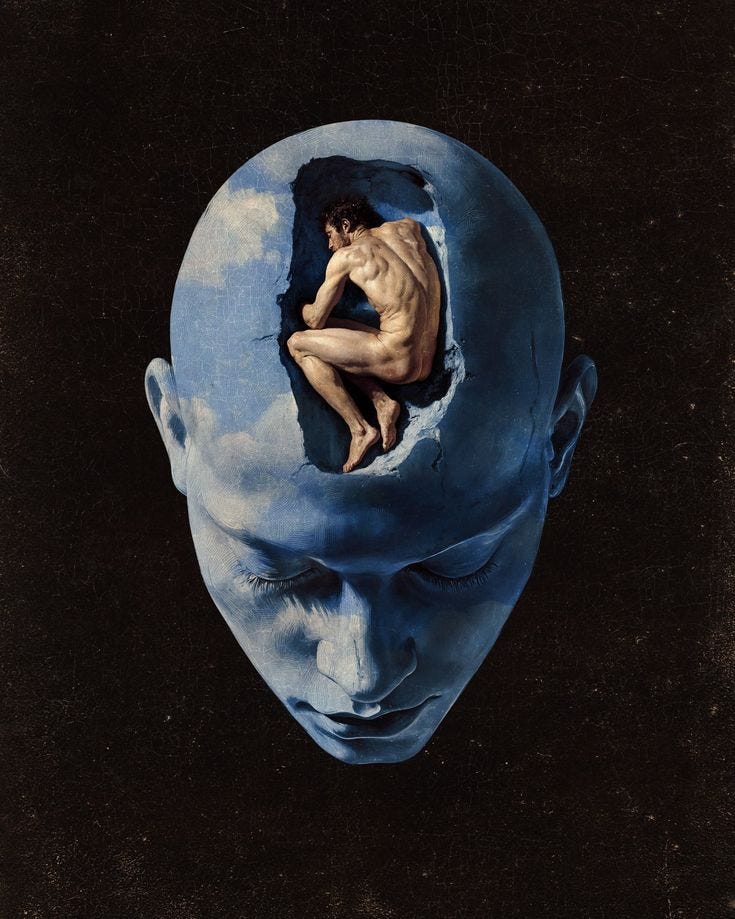

Set aside the cultural split and the picture becomes simpler. The qualities that guide a scientist through discovery are the same ones that guide an artist through expression. Noticing connections, recognizing patterns, imagining possibilities, these are shared capacities. All forms of creativity begin with the same mental groundwork.

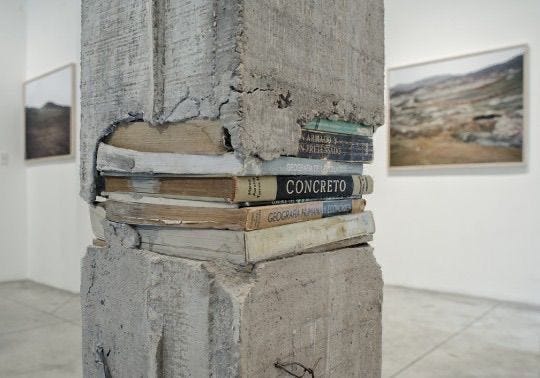

Analogy. The mind’s most instinctive tools. We make sense of the unfamiliar by relating it to something we already understand. Scientists depend on analogy to test ideas and model new concepts, while artists use it to reveal meaning or emotion. In both cases, analogy serves the same purpose: it makes the abstract graspable.

Pattern recognition. We have a tendency to search for structure. Whether in data, sound, or visual form, we are always detecting patterns. This ability fuels scientific insight just as strongly as it shapes artistic sensibility. In both contexts, pattern recognition helps us find order in complexity. Of course in different degrees, but the principle is the same.

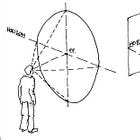

Visualization. The ability to see ideas before we can articulate them. Scientists visualize models, mechanisms, and relationships; artists visualize forms, colors, and imagined worlds. In both domains, visualization is the first step toward making an idea real.

Intuition. A quiet guide that precedes explanation. Long before logic confirms a direction, intuition suggests one. Artists rely on it instinctively, yet scientists lean on intuition far more than the stereotype allows. Often, it is the beginning of discovery in both fields.

Metaphor and modeling. A metaphor in art and a model in science both translate complexity into something the mind can hold. Each maps the intangible onto the tangible, allowing abstract ideas to take shape.

What Neuroscience Shows Us About Creativity

Neuroscience offers no evidence for a strict divide between artistic and scientific thinking. Creative thought engages widespread networks involved in memory, imagination, perception and reasoning, rather than separate art and science regions of the brain (Chatterjee 2014).. Even emotion and intuition, once viewed as irrelevant to scientific work, are now understood to support complex reasoning (Damasio 1994). In this sense, the brain quietly confirms what culture often obscures: creativity arises from the same neural architecture, no matter the form it takes.

Why reuniting science and art matters

What I ultimately hope to emphasize with this essay is simple: we need to stop labeling ourselves and others as “art people” or “science people.” These categories narrow our sense of possibility and ignore the reality that growth often happens at the edges where disciplines meet.

We should give ourselves permission to move between science and art, to combine ways of knowing, and to learn from people who think differently from us. Neither science nor art is superior; each offers a vital perspective on the world. And when they inform one another, our collective understanding becomes fuller and more capable of addressing the complexity around us.

The future belongs to the minds that refuse the divide.

If this felt like a conversation you connected with, these essays might resonate with you even more:

this is me!! I absolutely loved this, as someone who is deeply interested in chemistry, I am also a creative at heart being a writer and a painter. I often struggle to find people like this as I currently am doing majorly STEM within my studies, but I paint, draw and read and write on here during my free time. the bridging of these two sides is ultimately what will create the innovators, and creative thinkers needed to fuel discoveries. thank you for this insightful piece <3

we would not exist without science nor without art. you explain it perfectly 🤍🤍